In Conversation with Mark Kermode & Jenny Nelson

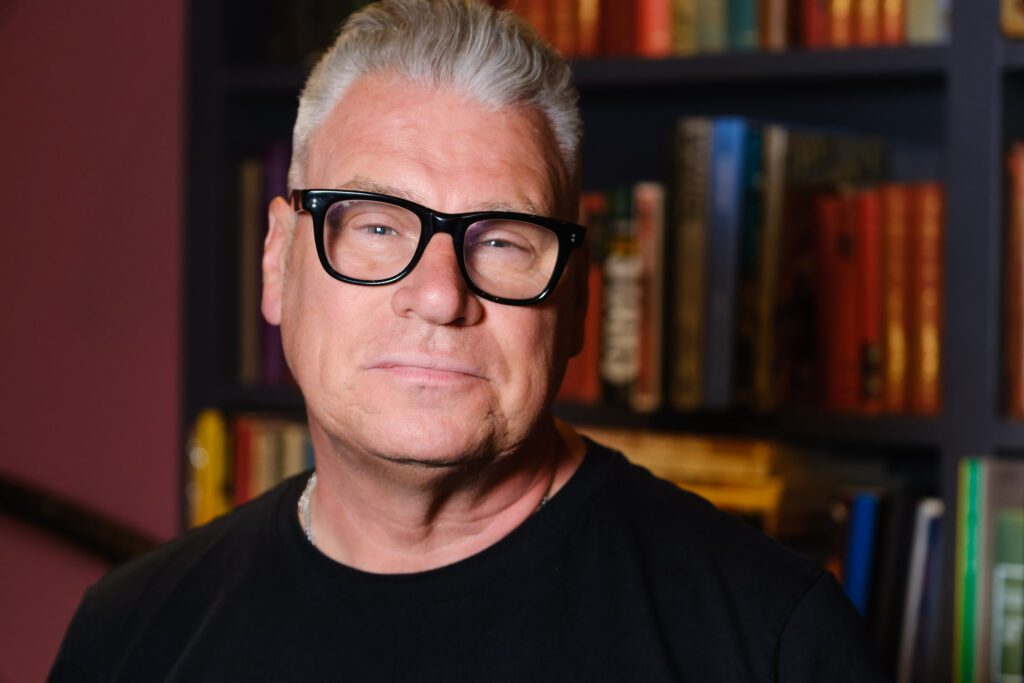

Mark Kermode is Britain’s most celebrated film reviewer. He’s a BAFTA member, Observer columnist and recipient of the BFI’s Outstanding Contribution to Film Criticism. To his fans, he’s best-known for razor-sharp and impassioned reviews. Thousands tune in weekly for his opinions on two popular podcasts: Kermode and Mayo’s Take, presented alongside Simon Mayo, and Kermode on Film. His latest project is a book that explores cinema’s most powerful soundtracks and their emotional impact. Mark Kermode’s Surround Sound: The Stories of Movie Music was written alongside Jenny Nelson, a radio producer and music programmer. The book asks: how can a film score make you cheer, shiver, cry or punch the air? And when does a soundtrack take on a life of its own? It’s a full-throttle trip down the glorious rabbit hole of film composition. Kermode and Nelson will appear in conversation on 7 November at York Theatre Royal, discussing the power of film music. Ahead of the event, we spoke to the pair about the new book, their personal favourite scores, as well as their involvement in this year’s Aesthetica Film Festival.

A: This book was 10 years in the making. Tell us about the writing process?

MK: It was 11 years ago that my publisher got in touch to ask what type of book I’d like to write next, and I said I’d love to focus on film music. I then came to discover that if you really love something, and the subject is huge, it’s actually very hard to organise your thoughts. I really wrestled with this thing, and at times it was like trying to nail jelly to the wall. I did interviews and a lot of research, but I just kept getting nothing written and instead ended up working on other projects. Then Jenny and I started working together at Scala Radio, and we did a weekly film music show together. My wife, Linda, pointed out that we worked really well together doing the show, so why don’t we work on book together. From that point, it was about two years until it was published. We literally wrote the whole book together. We would swap chapters between us and pass it backwards and forwards, so it really was a complete collaboration.

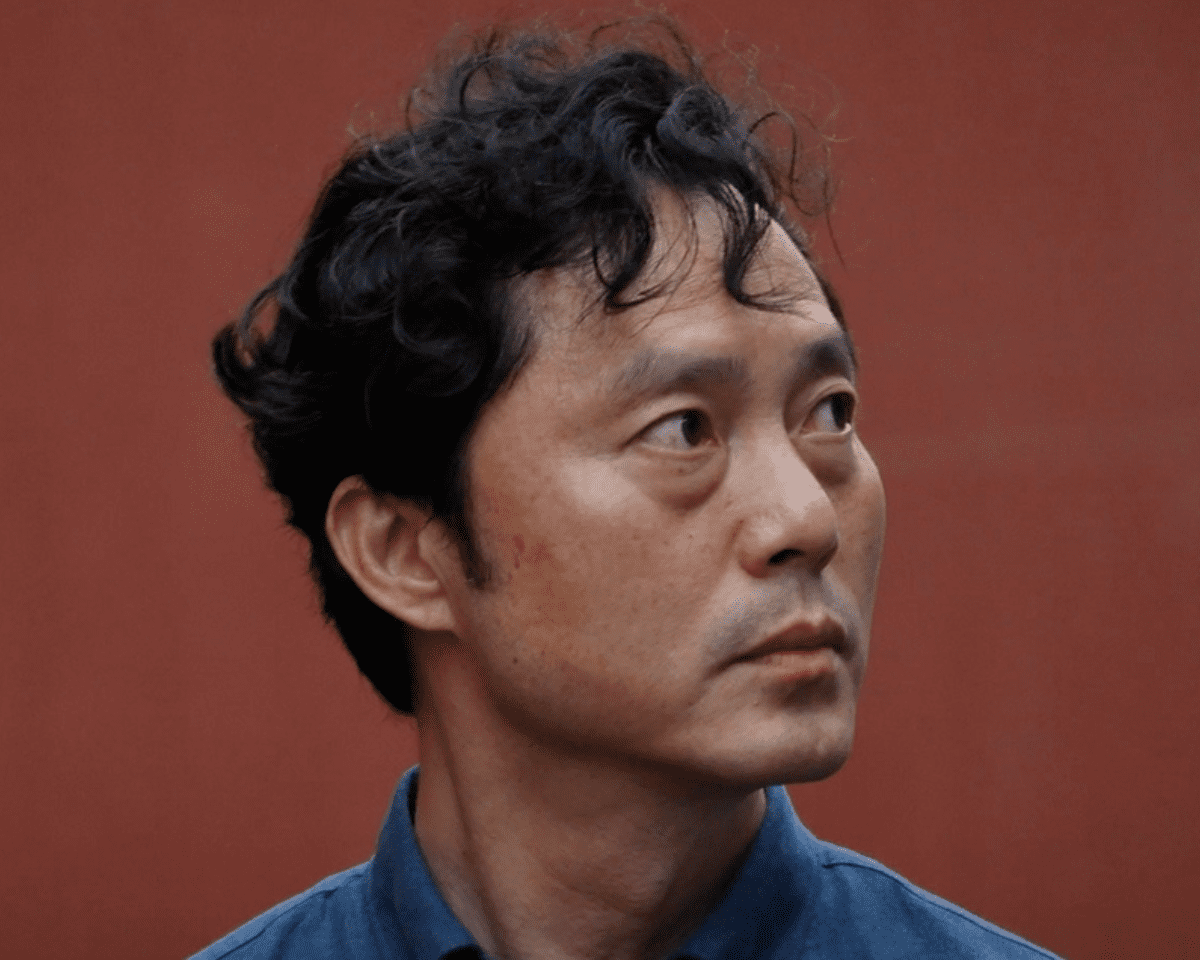

JN: When I first met Mark in 2019, I knew he was working on this, and I’d written a book of film music previously. I thought I was being very unsubtle in my attempts to be part of this project, and asked if I could do anything or help with interviewing composers. So, it was a real joy when he asked me to collaborate with him on it. We’d been working together for a few years at that point, so I knew his tastes both film genre wise but also musically, so I was able to reflect that in the book.

A: This is not the first book for either of you. How did working with another person shape your approach to writing?

JN: I found it really helpful because we worked out a structure for our chapters. We had a vague discussion on what would go in each and then it just happened very naturally. I knew there were film scores that Mark was particularly passionate about, so there were times where I was able to say; “add more of you,” because those personal experiences are what the book is all about.

MK: If you listen to a radio programme, you hear a presenter talking but you are not just listening to them. You are listening to them and their producer. We wanted to write the book in the same way. It’s in the first person, which is from me “presenting,” but we wrote everything together exactly as we would do in the radio show. That feels like the best analogy for how this came about. I wrote The Movie Doctors with Simon Mayo, but that was clearly one chapter from him and one chapter from me, so this was a very different approach. And it was definitely a successful collaboration, because after eight years of not hitting a deadline, we didn’t miss a single one.

A: The book is the story of movie music and the emotional resonance they can have. Which film score do you first remember really resonating with you?

MK: The very first soundtrack LP I ever owned was Dougal and the Blue Cat, which was from the feature length Magic Roundabout. My mum bought me the record and it turned out to be the entire soundtrack of the film, all the words and everything. It was literally the whole film from beginning to end. So, as a kid, I thought that was what film albums were. A bit later on, when I was listening to the soundtrack of The Sting (1973) and it was just the tunes, I couldn’t figure out where the rest of the film had gone. The guy in the shop had to explain to me that that’s what soundtracks are. I remember thinking: “oh, maybe the music is enough to tell the story.”

JN: I wasn’t a massive collector, but I grew up in the 1990s, and the music from Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet really stood out to me. I bought that album and I loved it so much. Then I saw that they’d released more music from the film, so I had to have that one too. That was an early introduction for me of what film music could be. More recently, Cristobal Tapia de Veer did the soundtrack for a Channel 4 TV series called Utopia. If I ever needed to get in the zone, I would listen to the finale music.

A: How has our relationship to film scores changed over time, with the emergence of technology and streaming?

MK: Back in the day, if I saw a film I really liked and I wanted to see it again, there wasn’t any video. You’d have to go back to the cinema or maybe wait until it came out on TV. But if you bought a soundtrack, you could kind of watch the film in your head, and if there was a book that it was based on, you could read that whilst you listened. I got into the habit of doing this and I’d also come home from a film, type up the story and make it into a little book. I’d even make a cover for it.

JN: At the moment, for all their faults, streaming platforms like Spotify have given us access in an unprecedented way. If you leave the cinema and think “wow, what an amazing tune,” you can be listening to it on your way home. It’s making things more democratised for the next generation of collectors, because the specialist shops could be very daunting, as well as often being quite male oriented.

A: How do you feel about the film scores coming out of the industry today?

MK: Score recordings are still happening. If you try and book into a recording studio in London, you’ll often find that it’s hard to get in. There’s almost no breathing space as every film production wants to have their scores recorded in the UK, because the players are so brilliant. There’s no question that the industry here is still booming. Things have also changed in terms of the prominence of female composers. There were always women working in this space, but there’s been an increased buzz in the past few decades. We’ve had Rachel Portman, Anne Dudley and Hildur Guðnadóttir all win Oscars. So it is changing, but unfortunately, it’s changing slowly.

JN: There is still a collector’s world out there. I think there’s been a resurgence in vinyl collecting and label like Invader have really invested in beautiful, limited edition records. But then we also have the bonus of streaming. I think the real issue is how scores are being made and whether AI is going to affect that. In the book, there’s a chapter about electronica soundtracks and the celebration of how they have democratised film scoring, as it allows more people to try it, even when budgets are lower. You can just be at your computer or in a home studio. That’s quite liberating and has allowed new musical voices to come through. In terms of diversity, it’s worth noting that Rachel Portman is the only woman composer to have received more than one Oscar nomination, and when you think of someone like John Williams, who has had over 50, this just isn’t enough. We interviewed Laura Karpman for the book, who is one of the co-founders of Alliance for Women Film Composers, and she talked about how many of the financial gatekeepers in the industry continue to choose male composers as they’re seen as more able to deal with the pressure of a big budget project. It’s ridiculous that in 2025, Laura, who has worked on huge films like Marvel’s Captain America: Brave New World, is still judged based on her gender.

A: You’ll both be appearing in conversation at Aesthetica Film Festival. What’s your relationship to film festivals?

JN: I was a trustee of the Cambridge Film Festival and I grew up in the area. It was a personal goal to return to where I’m from and make sure that the people there had access to film. I got a real insight into the running of an event like that, and the ongoing passion that comes from usually a very small team. As a punter, I studied in Edinburgh and volunteered at the Edinburgh Short Film Festival. When a festival is in a beautiful city, it’s even better. You’ve got wonderful films to watch in great cinemas, and then you can spend time in a lovely location.

MK: I was very proudly involved with the Shetland Film Festival for 17 years. My partner Linda and I were both programmers. It’s not like anywhere else – it’s closer to Norway than Scotland. The organiser, Kathy Hubbard, started out by showing films in the Garrison Theatre and then they built this amazing arts centre called Mareel. The thing is, people weren’t coming to this festival if they didn’t want to be there, it was for the people in Shetland because it’s so far from anywhere else. It had a real community feel and you’d show the films and people would go and retire to the bar together. Like Jenny said, festival organisation is hard work, but when they’re at their best, they’re a fantastic melting pot of people and ideas.

A: Mark, you’ll also be scoring a silent film with your band, The Dodge Brothers. Has performing shaped the way you view film music?

MK: Neil Brand, who is the maestro behind the band scoring silent films, has done a lot of research into what you would have heard before synchronised sound. The first few decades of filmmaking are a silent pursuit, but there was always music. Back then, you’d get little orchestras at the cinema. Neil came up with this idea to try and replicate this, which is to just knock it together on the spot and improvise. I remember very clearly saying to Neil, “well how is this going to work? You can’t have a whole band improvising.” And he said that if you watch the screen for the mood and my left hand for the key, we’ll be fine. That’s how we started, and our first gig was at the Barbican a week later. In terms of how it changed my understanding of film music, it was that thing of watching for the mood that really stuck with me. If you see Neil playing a film, what he does is alchemical. It’s kind of magical. He’ll pick up on the story and enhance it. He’s one of the greatest film musicians I have ever encountered, because he’ll not only respond to the film but also to the crowd – playing to a comic element or a melancholy scene. Sometimes he’ll score it against the way that the film wants to be played. It’s completely transformed my understanding of the way music both enhances and changes a film.

A: You’ve mentioned being part of festival in Shetland and Cambridge, and Aesthetica Film Festival is based in York. What role can film festivals play in fostering the creative industries outside of the typical hubs like London?

MK: Jenny and I both live in Cornwall, so our lives exist outside of London. I think this London bubble only makes sense to the people who are based there. There are so many things that are happening outside of major cities like London or Los Angeles, all of the time. We’re lucky in Cornwall because there are some brilliant cinemas, like the Newlyn Film House and the Plaza. There is so much cultural life here. In terms of film festivals being embedded in the local community – that’s when they’re at their very best. The industry needs to move past making people feel like they need to be in London, because you don’t. It’s the same for Aesthetica in York. When a festival is embedded in the community, it will have a life of its own. It will have a vibrancy. They have to be for the local audience first, and then everything else will fall into place.

Words: Emma Jacob

Join us for Mark Kermode: In Conversation with Jenny Nelson at York Theatre Royal on 7 November. Book Your Tickets Here.

Discover the full Beyond the Frame programme here.